This guide covers some of the fundamentals of shipping, including key players, terminology, documentation, incoterms, and how they can affect both your shipment and your freight costs.

Meet the Key Players

Carriers

Freight doesn’t move itself. Carriers are the companies that own the ships, planes, like Maersk and American Airlines. They typically don’t arrange the movement of freight beyond the port to port (or airport to airport) segment of the shipment.

Carriers sell bookings on their vessels, typically through third-parties (although they will offer services directly to very large companies). In the US, some non-carriers also sell bookings through a legal arrangement called NVOCC (non-vessel owning common carrier).

Forwarders

As the Freight Forwarders guide described them, “think of them as travel agents for freight, the experts who understand how the end to end shipment process works.” Some forwarders do sometimes also act as carriers, most commonly by also operating a truck fleet. Similarly, the big international couriers also own and fly cargo planes.

Customs Brokers

Customs brokers specialize in customs filing and clearing, as explained in the Customs Process guide. Freight forwarders either work with a customs broker as an agent or handle customs broking in-house. See more in the Freight Forwarders guide.

Third-Party Logistics Providers

Third-party logistics providers (3PLs) take on some or all of a company’s distribution and fulfillment services. Many larger forwarders also provide this service. This form of outsourcing is covered in the Third-Party Fulfillment guide.

Shippers

The only key player left is you. Whatever you call yourself, the freight industry calls you a shipper. For outsiders, this seems rather confusing but as forwarders and carriers set it, you are the person wanting to “ship” the goods.

Key Freight Terminology

Door To Door & Port To Port

This basically describes whether the shipment service provided is between ports or from/to another destination that requires trucking or railing services. The shipment leg between the export country and the import country is called the main transit or main leg. If the forwarder responsible for arranging this leg is also picking up the shipment at the factory, the shipment is called door to port. Similarly, port to door covers the main transit from the foreign port to final delivery. In door to door, the forwarder is handling the entire shipment.

Multimodal

The humble shipping container not only revolutionized international freight, it also revolutionized international trade and global economic growth. Multimodal simply means shipping by container. Once a container is “stuffed” with a shipment, it moves by road, ocean and/or rail until it is finally opened somewhere in the US. The whole process is so streamlined that inland cities like Denver or Chicago can act as ports, complete with customs clearance, deconsolidation (we get to that soon) and as the named place for some incoterms (ditto). These “inland ports” are usually referred to as inland freight interchanges.

Some key multimodal terms that you should know are:

- FCL (full container load). This means that you are paying for a whole container which, depending on your load size, may be cheaper than a less than container load The load doesn’t have to fill the container, as for, say ¾ loads booking FCL is cheaper than booking LCL.

- LCL (less than container load). Booking LCL means that your shipment is taking up only a part of the container and will almost certainly be shared with other shipments in that container.

- Consolidation/Deconsolidation. Consolidation is the process managed by the forwarder or carrier whereby the LCL shipments sharing a container are “stuffed” together. Deconsolidation is the opposite, that happens near a port at the end of the port to port leg.

- Intermodal. This term is often used interchangeably with multimodal, but there is a difference. With intermodal more than one forwarder is used, meaning there will be more than one bill of lading, and more communication required.

Trucking

FTL and LTL are the trucking equivalents of FCL and LCL, namely a full truckload shipment and a less than truckload shipment. US regulations require truckloads to be charged by a complicated method called freight class. Most products get classified by density. This freight class calculator estimates the freight class for density products. It also goes into detail about how freight class works.

Dimensional Weight

Freight class may be complicated, but other modes of transport can get that way too. Very light shipments that take up much more space than their weight would indicate are charged by dimensional weight, that is the weight at which your shipment’s dimensions would be reasonably profitable to carry. Each mode, ocean, air, trucking in other countries, have their own formula. In fact, every shipment is charged at the greater of actual weight or dimensional weight. That weight is called the chargeable (or billable) weight. Dimensional weight is also called dim weight, volumetric weight or cubed weight.

You don’t need to understand how it works, but don’t be perturbed if your shipment is very light and your requested freight quotes come back charged at a very different weight than you requested. Use this chargeable weight calculator to find out the freight class for density products, and to learn more about how freight class works.

The Key Freight Documents You Should Know

Commercial Invoice. This is the normal proof of sale, provided by the supplier to the importer, and in itself is not a freight document. It becomes one because Customs requires it for clearance. The Ordering guidecovers where this document fits in with negotiation.

Certificate of Origin (COO). Your supplier will prepare this in conjunction with their chamber of commerce. This document is also required by Customs for clearance because it helps identify banned items and duty payable. Your forwarder will require this when the Shipper’s Letter Of Instruction document (below) is prepared.

Material Data Safety Sheet (MSDS). This document only applies to hazardous goods and is usually provided by the supplier. Again, your forwarder will require this when the Shipper’s Letter Of Instruction (below) is prepared. This document is covered in more detail in the Product Research guide.

Fumigation Certificate. This document is only required if wood, and some other natural products, are included in the shipment. This most often applies to pallets and crates. Your supplier must arrange for this. Again, it required for customs clearance, and your forwarder will need it when the Shipper’s Letter Of Instruction (below) is prepared.

Freight Forwarder Contract (“T&Cs”). Like any other agreement that you sign with a service provider, you are required to sign off on their standard terms and conditions before they work on your shipment.

Power Of Attorney (POA). Like the commercial invoice, this is a widely used document outside the freight industry. By your signing one of these, your forwarder can deal with Customs on your behalf. You’ll sign a POA at the same time you do the T&Cs.

Shipper’s Letter of Instruction (SLI). With the above forms ready to go, this document kicks off the shipping process. It is your order form, proof that you are purchasing from the forwarder. This document is covered in more detail in the Request For Freight Quote guide.

Booking Confirmation. This is your receipt for the main transit, whether ocean or air. The carrier provides it to your forwarder, who should forward it on to you. In some cases, the booking confirmation number is also the shipment tracking number.

Bill of Lading/Air Waybill. These very similar documents used for ocean freight and air freight respectively, are the contract of carriage for the main transit leg. Like any other contract, it has terms and conditions which limit forwarder and carrier liability. Your forwarder prepares the bill of lading. This document also provides proof of ownership of the goods in case of damage, theft or loss. Some forwarders add the shipment tracking number on this document.

There usually isn’t the same formality with booking pickup and drop-off. There’s a lot more flexibility in making arrangements with a local trucking company than with container ship or airline carriers. Emails are usually the only documentation required.

Packing List. This is your receipt of goods at delivery. It is attached as a pouch on the goods and also emailed ahead. It is only required when shipped goods are packed into larger units, like a container or an aircraft console. The supplier completes this form, although the forwarder will also complete one if the goods are re-packed at their warehouse.

The Key Freight Documents For International Shipping resource has more information on most of these documents.

Buy Price vs Landed Cost

Landed Cost

When you are negotiating a price with your supplier (covered in the Negotiating Strategy guide), it’s tempting to get fixated on the buy price. The lower the buy price the better the markup. Right? But, there are two other costs to take into account before those goods are safely in your inventory. They are customs charges and freight costs.

LANDED COST = BUY PRICE + FREIGHT COSTS + CUSTOMS CHARGES

The Customs Duties guide goes over how to get estimates for duty costs. And, getting reliable freight cost estimates from a freight rate calculator is covered in the Mode Selection guide. But your freight charges will vary depending on how much responsibility you are willing to take.

Your supplier will probably only arrange all the freight if they can make up for it with a higher buy price. Similarly, you will only pay all the freight if you can make up for it in a lower buy price. But it’s not uncommon for inexperienced buyers to squeeze a better deal out of a supplier, but fail to realize the consequences when the supplier accepts a lower buy price, in exchange for switching incoterms. That might seem harmless, but, switching from FOB to EXW, for instance, might have wiped out all the gains made by the cheaper buy price. So what are Incoterms?

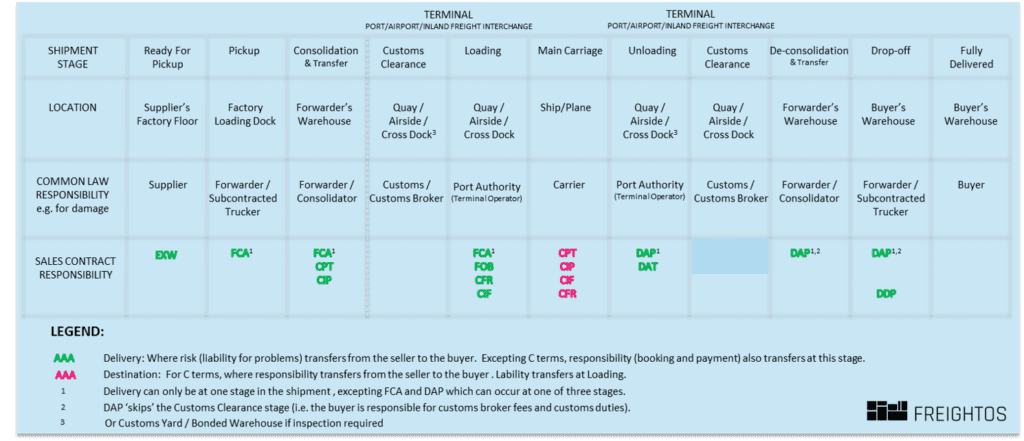

Incoterms

This gets a little boring but it’s really, really important. Incoterms are standardized freight terms that are used in international sales agreements. There are eleven of them in all, each differing in where, during the shipment, the responsibility (arranging and paying) and liability (for resolving any problems) transfers from the seller to the buyer.

Most suppliers have a preferred combination of incoterm and selling price. Often, that’s CIF (Cost, Insurance and Freight), which means their responsibility for the goods ends at the US port. It is commonly used, however, for smaller buyers this incoterm (and the three other incoterms starting with the letter “C”) are disasters waiting to happen. This is explained in the Freight Forwarders guide.

The safe (and more common) incoterms that you should be negotiating, are:

- EXW (Ex Works), where you take full responsibility and liability from factory pickup.

- FCA (Free To Carrier), where you take responsibility and liability once the shipment is handed over to the carrier, typically for consolidation at carrier’s premises near the port.

- FOB (Free On Board), where you take responsibility and liability once the shipment “crosses the ship’s rail.” Technically FOB wasn’t designed for freight that goes into containers or airplanes, but it does work well for full container loads. However, it shouldn’t be used for LCL or air freight, because they need to be consolidated before they are handed over to the carrier. Also, for air freight, there is no “ship’s rail.”

Stick to this advice, and you probably won’t need to know much more about incoterms. They do get complicated. The following table brings the main points together. For more detail, turn to the Incoterms In Plain English guide.

Calculating Landed Cost

Now that you get landed cost and incoterms, you can bring it all together to calculate landed cost. Say you want to know what your target buy price would be with EXW and with FOB:

- Use this freight rate calculator to quickly find this out. Work out the door-to-door freight rate (for EXW) and the port-to-door freight rate (for FOB) to get the two different freight costs.

- Then, simply add your customs duty estimates to calculate landed cost for both freight terms.

- Now you have your target buy prices for negotiating either incoterm.

You will find a host more key freight terms in this freight term glossary.