And both shifts will have major ramifications on customers – importers, exporters, and online sellers.

No end to end-to-end

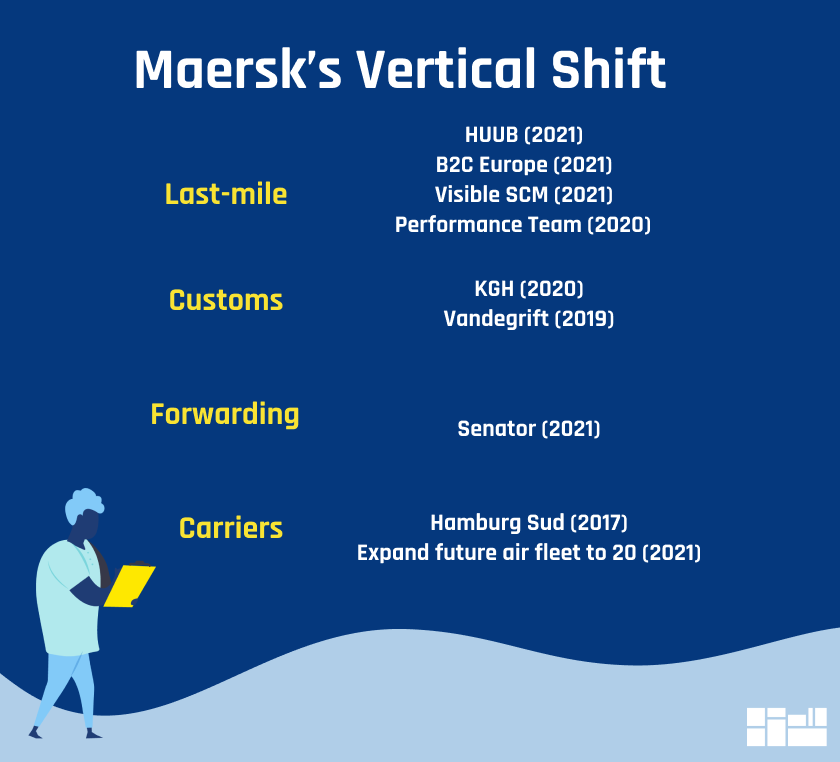

Maersk has unabashedly championed vertical integration for years, advocating an “end-to-end” strategy. The ”end” they refer to – whether it’s forwarding, fulfillment, or platforms for B2B or B2C sales – remains fairly ambiguous, spanning an acquisition of fashion logistics company HUUB in September 2021 to an investment in rapid fashion production company Unmade. More on Maersk’s transition to an end-to-end provider can be found in this 2020 report.

Accelerating the shift

Late 2021 saw Maersk continue to shift towards vertical integrations, with acquisition of Senator, a German freight forwarder for $644 million dollars. Even closer to end customers, in August, Maersk acquired Visible SCM, a Utah-based B2B/B2C company, which handles over 200,000 orders a day across nine fulfillment centers, as well as a European counterpart

On the horizontal carrier integration front, Maersk has doubled down on its extension from ocean consolidation (Hamburg Sud, 2017) to air cargo, increasing Maersk Air by 33% with three leased cargo planes and two new Boeing purchases.

Behind the Maersk shift

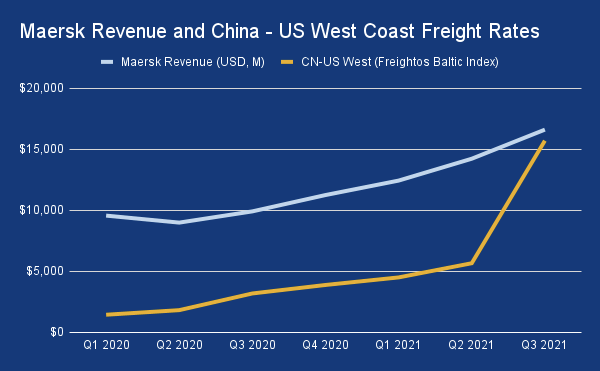

The original 2016 driver for this shift seems hard to believe in today’s freight environment: a focus on long-term business viability spurred by ocean freight rates so low that they precipitated the bankruptcy filing by ocean carrier Hanjin.

Maersk isn’t alone in this approach, although it is the farthest down the rabbit hole. CMA CGM, the third largest ocean carrier, is increasingly oriented towards shippers, with the vertical acquisition of CEVA in 2019. And, not to be left behind, it’s also pursued a horizontal integration strategy, acquiring a growing fleet of airplanes.

From a carrier perspective, these shifts are not without risks. Specifically, the more extensive the carrier and forwarder footprint, the greater the risk the carrier pose to forwarder business. For a forwarder, refraining from working with Maersk today is expensive because it removes 17% of global shipping capacity. However, more shipper engagement could, eventually, make the cost of collaborating with Maersk much higher than the cost of not collaborating.

[optin-monster slug=”qroan7mfdqfszfr5xkuf”]

Enter Big Tech

While Facebook is looking at virtual reality, Alibaba and Amazon are looking more at freight. The Loadstar found that Alibaba has a minority stake – by way of Cainiao – in Transfer, an ocean liner owned by Worldwide Logistics Group. Meanwhile, while Maersk was expanding its air fleet to 20 aircraft, Amazon recently passed the 85 mark.

Combined with more activity at their regional hub in Germany, Amazon has clearly become a major global cargo airline.

One goal, two different motivations

While carriers and tech companies are drifting towards each other, both have different motivations.

Carriers are intent on stepping out from being an infrastructure layer. These carriers seek to improve retention, relevancy and margins through a more direct relationship with shippers instead of letting forwarders or eCommerce fulfillment companies reap the benefits on goods that carriers move.

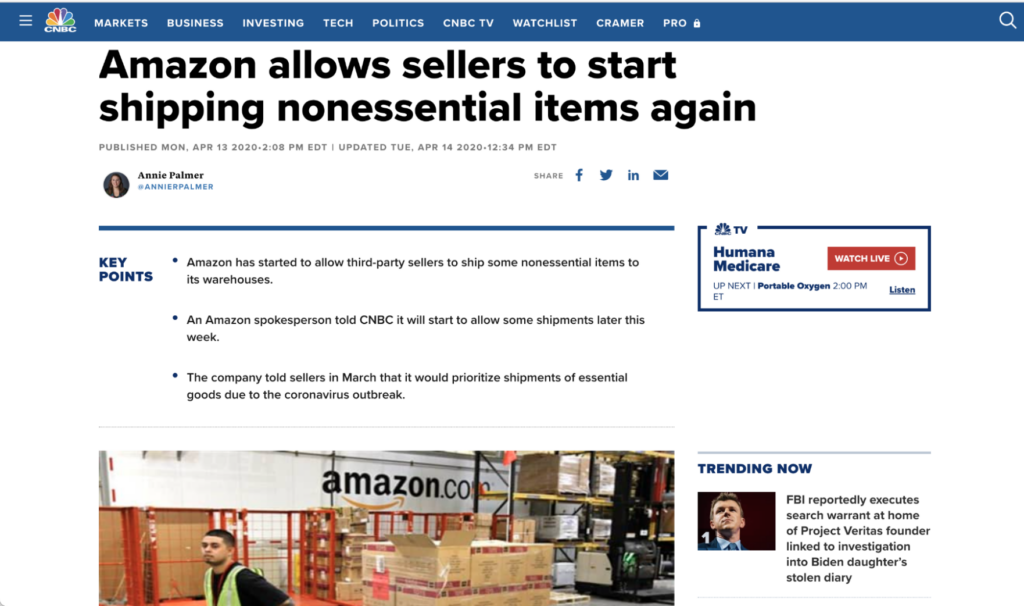

On the flip side, the large tech companies’ drive to actually move goods for customers is likely centered around reliability. Amazon has made a habit of excelling at logistics to retain end customers and third party sellers. Reliable freight is a critical part of this, which explains Amazon’s migration towards increased ownership of last-mile delivery over the past 15 years.

For a company like Amazon, 2021 underscores the importance of owning middle-mile capabilities to ensure resilient inventories. Like cloud computing or last-mile delivery, Amazon quickly realized that to provide the level of service they need, when they need it, assets must be owned.

The difference… and the looming carrier threat

While tech companies are making the shift towards asset-owned international freight to improve reliability for existing customers, Maersk has more ambitious plans: direct competition withAmazon and other 3PLs. This motivation explains the secondary heading in the press release around Maersk’s acquisition of Visible, the eCommerce delivery company:

“Maersk customers in the Business-to-Consumer segment will be able to reach 75 pct. of the U.S. direct to consumer market within 24 hours, 95 pct. of the U.S. within 48 hours.”

Similar sentiments were shared when Maersk acquired B2C Europe in October 2021:

The company’s offering consists of labeling services, pick-ups, sorting parcels, linehaul and injection into the last mile delivery network of 100+ connected carriers across Europe, including full returns logistics mainly covering 35 European countries. B2C Europe is operationally present in four key European E-commerce countries (Netherlands, France, United Kingdom, and Spain), and has offices in China.

But what does this mean for shippers?

For shippers, this now means a plethora of options. Specifically, today, an importer could today import air cargo using an ocean liner, a traditional freight forwarder, a digital freight forwarder, a digital freight marketplace like Freightos.com, an online platform like Amazon, or their own existing supplier.

Of course, working with tech players that ship or ocean liners owning more of the shipper value chain – introduce opportunities but also some major disadvantages.

Amazon as a carrier

On the tech aggregator side, this is not the first time Amazon would provide global freight services. The company has steadily increased its own freight activity while extending services to customers since registering as a forwarder in 2016. With integrated international freight, importers could get improved pricing (after all, Amazon is making their money further down in the value chain), as well as the simplicity of a one-stop shop, and, of course, Amazon-level reliability.

On the flip side, Amazon sellers are already nervous about the potential for Amazon to copy their product; providing more insight into manufacturing may be too much transparency.

In addition, more and more sellers are making their goods available across multiple platforms, including their own websites. Shippers using Amazon to ship to Amazon warehouses would either have to split shipments prior to exporting, which could create more complexities or pay Amazon to split the shipment after import. Either of these would make selling on other platforms more challenging.

Carriers as tech companies

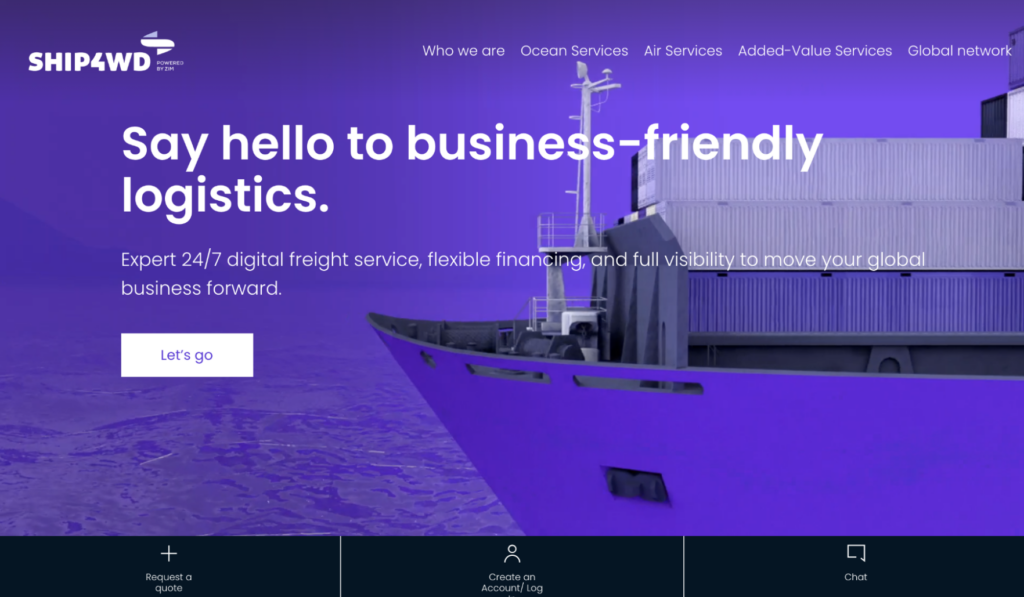

Ocean liners already get half of their business directly from shippers, while watching freight forwarders resell their services and walk away with a 15% margin on the other half. It’s therefore no surprise that a litany of freight infrastructure companies are doing everything they can to step out of the lower margin role (like Zim’s Ship4wrd or DP World’s online platform).

This isn’t necessarily a bad thing.

Ship4wd, Zim’s new digital forwarder

A direct carrier/shipper relationship introduces more flexibility for how any given carrier manages its own capacity. Twill’s experimentation with getting rebates for agreeing to roll containers or the potential for small businesses to secure faster booking, are proofs of this potential.

But while carriers may be better equipped to provide unique services related to maritime freight, that doesn’t make them a better alternative for shippers every time. Forwarders, with access to a range of carrier services, can potentially provide better service across multiple carriers. As the CEO of CH Robinson said ona recent earnings call:

In today’s environment of global supply chain disruption, customers are looking for solutions that span the globe across all modes. An ocean freight solution alone doesn’t solve for the problem that customers are facing, neither does a standalone truckload or an LTL solution. And we continue to be uniquely positioned to serve customers during this time of disruption and beyond to orchestrate and end supply chain success for these customers.

For small or midsize businesses, procuring freight directly from a carrier may be cheaper, depending on the extent to which carriers aim to maximize margins. But forwarders’ aggregate buying power across multiple small importers, which gives them the ability to pass on reduced costs to smaller companies that can’t otherwise support them. This isn’t just about purchasing power. In tight capacity environments, it’s unlikely that a small business could compete with a multinational. Under the umbrella of an aggregator, they just might.

A new tactic in the battle

Until now, carrier inroads have sounded like a net gain for shippers; the potential for new, direct services at potentially lower prices directly from carriers alongside the option to continue booking more flexible services from forwarders. However, if correct, the recent murmurings of Maersk cutting out forwarders, (see this Loadstar article), change the tone of the conversation.

With direct shipper booking from carriers, shippers have more options and could make the best free-market choice, between forwarders and carriers. But if forwarders are forcibly removed from the loop by carriers refusing to sell to intermediaries, options are reduced, not increased, which likely would not play to shippers’ advantage long-term.

The forwarder ramifications

Facing carriers long incentivized to extend down the value chain (and suddenly empowered with an adrenaline shot of capital), forwarders must be more ready than ever to differentiate their value and services.

Each forwarder will likely try to carve out their own differentiation but chances are that it will be reflected in freight specialization and regional specialization. The tendency toward regional specialization is strong; even for digital forwarders, it seems to be the dominant strategy (e.g. Flexport in the US, Beacon in the UK, Forto in Germany, K-Log in Latin America).

The ability for shippers to diversify among carriers by booking through a forwarder will remain a powerful draw for forwarders as well. And finally, as trite as it may sound, there are likely some shippers that will be less inclined to push more business to carriers, not only due to concerns with a lack of diversification but also because it stings to know that while rates have increased by 10x in one year, Maersk reported a $5.5 billion Q3 profit that was “better than the best year ever for the company.”

What’s next

The shaping trends of 2021 – limited capacity and rampant demand – are unlikely to continue on forever. Which means that, eventually, freight will sway towards being slightly more of a buyer’s market. Increased competition across forwarders, tech companies, and carriers should continue to help introduce more innovation to the industry. For shippers, this will likely drive innovation; online freight quoting only started to really take off once competitors started to raise the bar.

Carriers, forwarders, and tech platforms all have access to different physical and digital capabilities. In addition, their customers (or prospects, in Maersk’s case) all have a range of needs that will shape their development priorities. While the way they implement these will differ, there is one thing that is certain; the relationship between carriers, forwarders, and tech platforms, which has been one of both competition and co-dependence, is entering a period of unease and potentially huge innovation.